The New York Post’s David Propper recounts the latest scientific fraud scandal under a cutesy-ironic headline:

Harvard behavior scientist who studied honesty accused of fabricating data: report

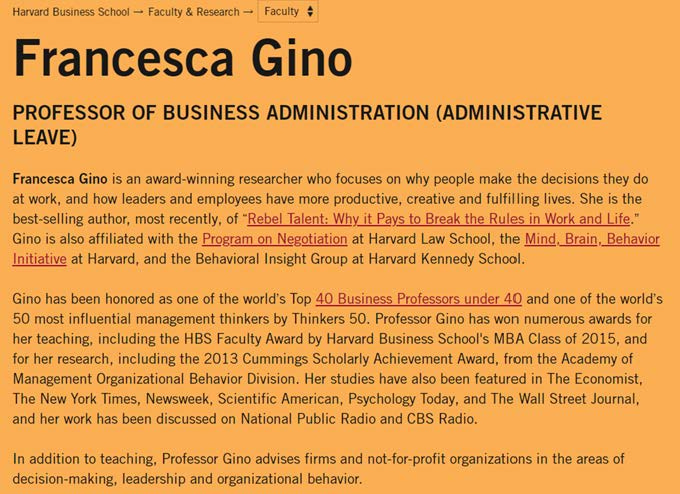

The scientist in question is Professor Francesca Gino. Here’s an image of her HBS faculty page:

Gino is a Harvard high achiever who gets plenty of press and media attention (Newsweek, Psychology Today, Scientific American, NPR, yadda). She has churned out 135 research papers since 2007 according to The Chronicle of Higher Education; that’s more than 8 per year.

Many of these of these studies were done in collaboration with other researchers, some of whom are no doubt peeing in their pants right now. It’s going to be a miserable summer for them, and the journals they published in, as all the tawdry details get sorted out.

But here’s the thing that leapt out when I read the story: the puniness of the studies Gino produced. They were all bite-sized and blurbable. Easy to swallow without much thought. No need to plumb the depths of the methods section—the results are just so . . . intuitive.

Some examples (not all of which may be implicated in the scandal):

Signing at the beginning versus at the end does not decrease dishonesty

Handshaking promotes deal-making by signaling cooperative intent

Artful paltering: The risks and rewards of using truthful statements to mislead others

Gino clearly has a winning formula: Take a mundane micro-behavior associated with conventional wisdom, and hoke up some lab-based game scenarios to assess it. If the results confirm the CW, publish the cute confirmation (“Handshaking promotes . . .”). If the results run counter to CW, publish a cute takedown (“Signing at the beginning . . .”). Either way, she ends up with near-perfect LPUs (Least Publishable Units) that are great fodder for media quotes. Plus they pad out an academic CV quite nicely.

Working in the fraudster’s favor is that these papers fly effortlessly through peer review. They are small-scale, stand-alone studies with intuitively reasonable results, and they don’t challenge well-established theories. Peer reviewers will not go all Sherlock Holmes on the deets. Just wave ‘em through.

Does this MO sound familiar? It should. Remember Brian Wansink, the (former) Cornell food researcher? He regularly produced tasty sound-bite research.

Cornell University marketing professor Brian Wansink is famous for surprising findings about food—e.g., that people eat more popcorn when it comes in bigger tubs, or that the characters on cereal boxes are drawn with eyeballs looking down, as if to make eye contact with children in the supermarket aisle.

Eventually his house of cards came tumbling down.

And then there is Nicholas Guéguen, the prolific French psychology researcher. He published lots of small ball studies with intuitively reasonable conclusions. An example is his “confirmation” of The Cinnabon Effect (which I fell for back in the day). Another is “Effect of a perfume on prosocial behavior of pedestrians”. There are many more.

When a few people raised doubts about validity of his work, Guéguen went to ground.

Academic science bears the responsibility for this mess. Grants and promotions depend entirely on publication metrics. Scientists have become increasingly careerist: they keep their heads down and conduct unobjectionable, incrementalist research on “safe” topics. The result is banality at best, fraud at worst. The entire enterprise is in decline.

It’s sad, really.

Peter Apps:

Harsh! But fair. This leaves little room for noodling around, trying something different, going on a hunch, exploring a counterfactual "what if?", questioning an assumption behind the Big Theory. It's like working in an Amazon fulfillment center but with longer bathroom breaks.

This salami-slicing, guaranteed results by the deadline version of science also suits funders, because it keeps the box-tickers and bean-counters off their backs, and is a perfect fit to modern academia where research projects are designed around what a post grad can be sure to get done before their grant runs out.