Sniffing Mummies for Science

And other scents from the ancient world

Active sampling of coffin headspace performed with sorbent tubes. From Paolin et al.

Quantitative sensory analysis is basically methodical sniffing: one evaluates the smell of interest using standardized rating scales and the results, averaged over multiple sniffers, yields a statistical profile of the scent. Combine this with chemical analysis—mass spectrometry to identify individual aroma molecules, and gas chromatography to measure their respective concentrations—and you get a good picture of the smell and its sources.

This combined approach has been applied successfully to foods, materials, and even body odor. Now a team of researchers has used it to analyze the scent of nine mummified bodies in the collection of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. Some of the remains date back to the New Kingdom (c. 1570 – c. 1069 BCE), when the highest quality of mummification was practiced, and others to the Late Period (c. 664 – 332 BCE) and even the Byzantine Period (3rd – 4th century CE) when the practice was in decline.

Given the balms and resins used in mummification, the preserved remains do not smell of organic decay: conservators have noted that the smell is generally pleasant. Yet until now, no one had assessed it systematically, much less scientifically. The research team here sniffed the mummies directly and also assessed their scent with analytical instruments. In a technique known as GC-MS-O, a coffin air sample is run through a split airstream: one portion goes for instrumental analysis (GC-MS), while the other goes to a sniffing port (O) where a person records odor impressions as each type of molecule exits the device.

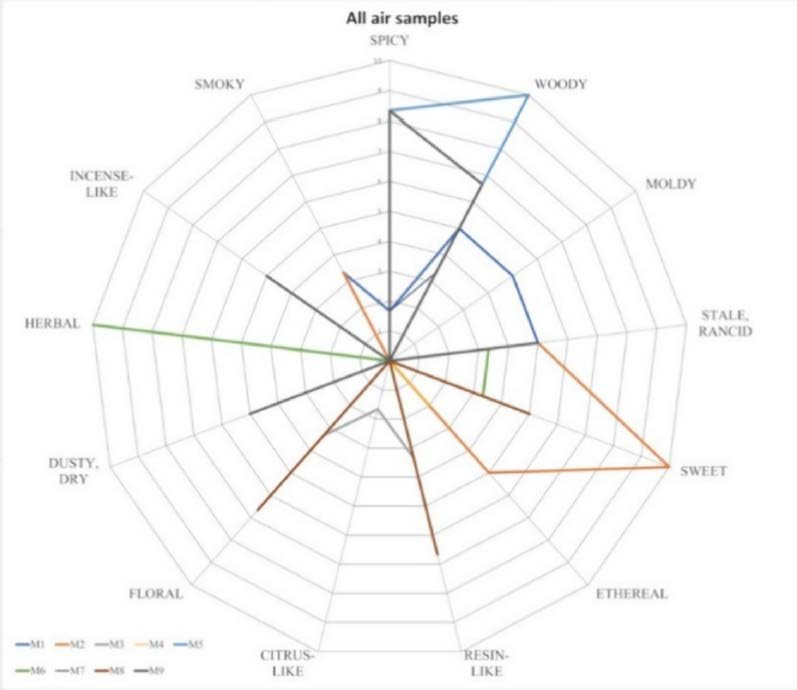

Here’s a spider plot representing the main smell vectors of all nine mummies, with descriptors woody, spicy, and sweet predominating, although stale and rancid show up as well.

Paolin et al. have an excellent grasp of chemo-olfactory analysis and its subtleties. For example, they are aware that mold growth in museum specimens is associated with smelly eight-carbon compounds (such as octanol, octanal, 1-octen-3-one and octanone) emitted by active mycelia. And they are honest enough to concede that their characterization of mummy aroma is complicated by the museum’s treatment of mummies with “pest oil.” Conservators use this aromatic blend of essential oils in lieu of potentially toxic pesticides to repel insects and prevent decay. But even with these provisos, Paolin et al. set a high bar for aroma analysis of mummified remains.

This was not the only fragrant news from the ancient world in recent days. There was this Agence France-Presse story published in Barron’s:

Smell Like A God: Ancient Sculptures Were Scented, Danish Study Shows

and a similar headline from the online magazine Archaeology News:

Ancient Greco-Roman sculptures were scented, study reveals

The latter story claimed that “sculptures were experienced in antiquity with more than just the eyes: they were engulfed in scent.”

The object of this fanfare was an article in the Oxford Journal of Archaeology by Cecilie Brøns, an archaeologist and curator at Copenhagen’s Glyptotek museum.

It is now widely held that ancient sculptures—that we know today only as white marble—were originally polychrome (sometimes garishly so) and often adorned with flowers, jewelry and textiles. Brøns theorizes that many ancient sculptures—esp. venerated cult images—were also scented. How does she arrive at this conclusion? Not through direct chemical analysis or by sniffing actual statues. Rather, she cites the writings of numerous ancient authors who note that priests and worshipers would apply waxes and resins to the surfaces of a statue, and that these materials likely were scented. Indirect evidence to be sure, but still intriguing.

On reading her paper, one is immediately struck by its tone. In contrast to the definitive headlines in the popular press, Brøns herself is cautious and restrained. In citing the ancient literary evidence, she is decidedly tentative—to the point that she often seems to undermine her own thesis.

For example, she notes that some inscriptions “imply the use of perfume, although this is not explicitly stated”, and that use of the term ganosis with reference to the surface treatment of sculpture with oils and waxes is “controversial”. (When Pliny and Vitruvius mentioned ganosis, it was with reference to sealing the surface of a wall painting to prevent the colors from fading.)

Similarly, when Brøns writes “these sources do not mention smell or scent, which, however, does not necessarily allow the conclusion that the oils used were unscented,” one doesn’t get the impression that the positive evidence for her thesis is overwhelming.

Her main case centers on the Greek island of Delos. Temple inscriptions found there refer to kosmesis (the act of adorning sculpture with textiles, ribbons, and jewelry) and the island is home to the ancient remains of a building where perfumes were manufactured. Having a perfume factory on your island might encourage a liberal use of scent in the local temples, no? It would be more compelling to see evidence of statue scenting in temples more distant from fragrance sources. (Brøns cites none.)

It is highly likely that waxes and resins were applied to sculptures to preserve the polychrome paint and provide a lifelike sheen. But there remains an alternative thesis. What if, despite the ancient quotations assembled by Brøns, these mixtures were scented as an afterthought, just as manufacturers put scent into floor wax today? Perhaps adding fragrance was simply a way to make the task of kosmesis less of a chore.

Emma Paolin, Cecilia Bembibre, Fabiana Di Gianvincenzo, Julio Cesar Torres-Elguera, Randa Deraz, Ida Kraševec, Ahmed Abdellah, Asmaa Ahmed, Irena Kralj Cigić, Abdelrazek Elnaggar, Ali Abdelhalim, Tomasz Sawoszczuk and Matija Strlič, Ancient Egyptian mummified bodies: Cross-disciplinary analysis of their smell. Journal of the American Chemical Society 147:6633-6643, 2025.

Cecilie Brøns, The scent of ancient Greco-Roman sculpture. Oxford Journal of Archaeology, published online March 3, 2025.

Priscilla,

Great question. Sweet is one the five basic tastes, but it is also useful as a smell descriptor. Vanilla (molecule = vanillin) and coumarin are two well-known sweet-smelling compounds. I could imagine instances where sour could be useful (the smell of curdled milk, yogurt, etc.). Bitter not so much, and salty not at all. Umami is not so easy to pin down as a taste--call it savory, perhaps. A lot of meaty or onion/garlic scents might qualify, but I wouldn't use it in a smell evaluation.

That is so cool! I would have loved to smell a mummy, lol! Thanks for sharing!

One question, though… Your article got me thinking about the classification of aromas. I would have thought that in a more professional setting, people only use “sweet” as a taste. Do you think they’re referring to compounds that create the impression of sweetness, like honey or ripe fruit or is there a more technical basis for using “sweet” as an aroma descriptor in this context?