Practicing the Wertz Catch on Alice Street

Farewell to a Boyhood Hero

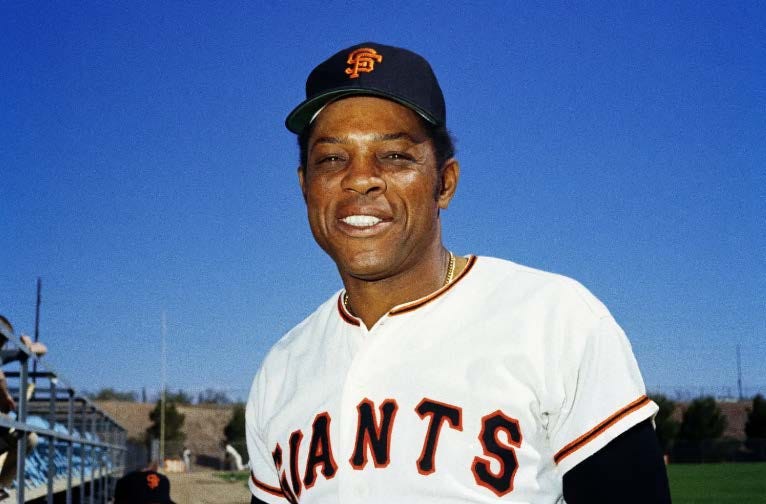

Willie Mays died peacefully yesterday at the fine old age of 93. He was one of the greats of baseball and a focus of my adolescence.

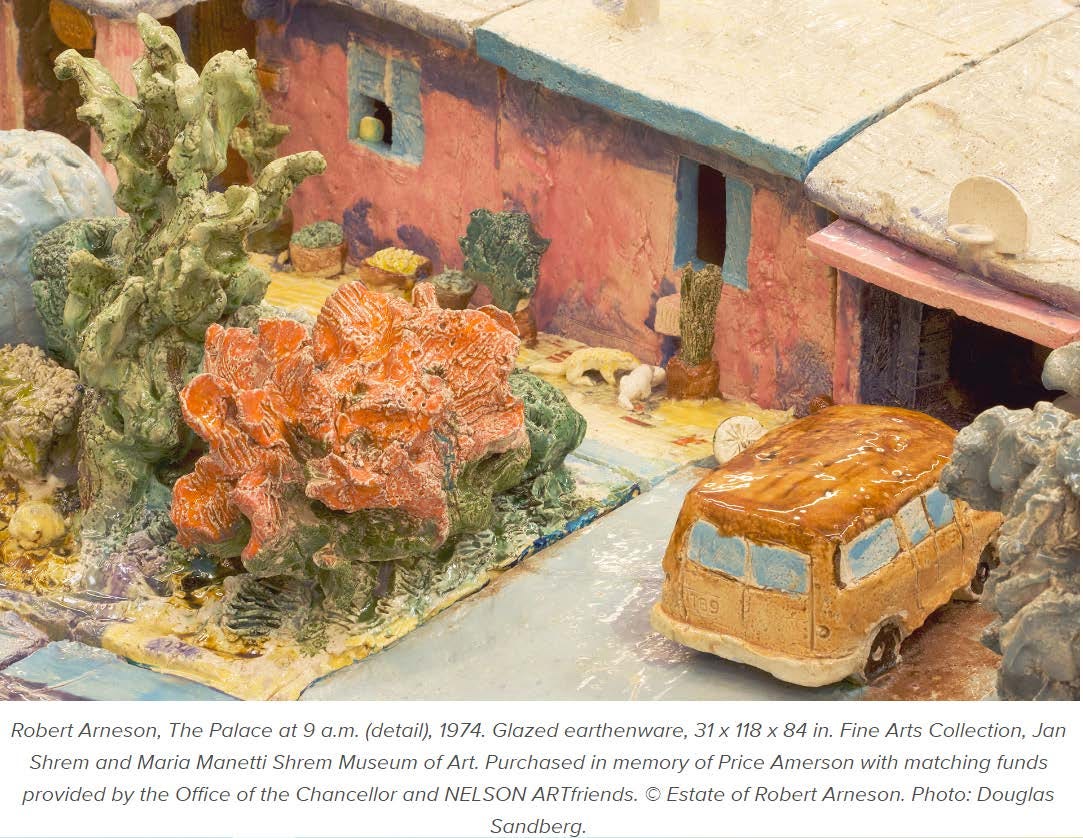

I grew up in Davis, California in the 60s. It was a campus town and my dad taught in the philosophy department. We lived near the edge of town on Alice Street—tomato fields stretched a mile north from there to the Hunts cannery. Bob Arneson and his family lived across the street. Arneson was on the art faculty at UC Davis where he created the inventive ceramic sculptures that became known as Funk Art.

Arneson’s garage was often filled with his ceramics—I recall, for example, a life-sized toilet complete with a glazed turd in the bowl. Another was a sculpture of a bronzed brassiere (his wife’s?) on a pedestal, an object of some wonderment to me and my fellow Cub Scouts when Mrs. Arneson was our den mother. Such was Bay Area life in the 60s.

Above: The Arneson’s house at 1303 Alice Street in Davis, as I remember it.

Leif, the oldest of the Arneson boys, was about my age and we hung out a lot. We must have logged hundreds of hours playing catch and fielding batted tennis balls. We were of course fans of the San Francisco Giants and we listened to most of their games on our transistor radios. We idolized many of them—Juan Marichal, Gaylord Perry, Willie McCovey, Bobby Bonds, and the rest. (I still have my Hal Lanier logo glove.) But above all, we were fans of Number 24, center fielder Willie Mays.

We imitated his nonchalant “basket catch” style of fielding a fly ball. We imitated his swing. But most of all we taught ourselves to mimic the Wertz Catch. It had occurred before we were born, in Game 1 of the 1954 World Series against the Cleveland Indians, but the film of it was engraved on our brains.

In the eighth inning, with Indians on first and second and nobody out, Cleveland first baseman Vic Wertz hit a drive to deep center field.

Mays turned his back to the infield and raced to the deepest recesses of the Polo Grounds where he caught the ball over his shoulder some 450 feet away from home plate. He quickly turned and threw the ball back in toward the infield, pirouetting as he lost his balance and his cap.

“I had it all the way,” Mays would say.

Above: The garage door at 1303 Alice Street.

With Leif standing on his curb, and me on my driveway, I would lob a high “fly ball” across the street on a trajectory that would land it a couple of feet in front of his garage door, which served as the imaginary center field wall. Leif would run to the door, catch the ball over his shoulder, then fire it back to me. Then it was my turn to charge toward my garage door. After hundreds of repetitions we got good at it.

Photo copyright Avery Gilbert

Above: Candlestick Park, July 6, 1969: Willie Mays batting against Phil Niekro with Willie McCovey on deck.

Willie Mays wasn’t a showboat, he wasn’t hyper-aggressive, and he wasn’t a braggart. In postgame interviews with broadcasters Russ Hodges and Lon Simmons he was always upbeat and genial. He was, to us, simply a good guy. He’ll always be my favorite ball player.