image: Joseph OBrien, USDA Forest Service, Bugwood.org

I’m always up for an interesting “molecules-behind-the scent” story. When this one from Scientific American popped up on my feed it seemed timely and worth a read.

What Gives Christmas Trees Their Crisp, Cozy Scent?

Learn which molecules are responsible for giving Christmas trees their distinct, crisp-yet-spicy scent

I was hoping for mention of specific molecules, or perhaps word of new research on key compounds differentiating the scents of Fraser, noble, and balsam fir.

Well, so much for my hopes.

The entire chemical content of this 600-word piece by Meghan Bartels boils down to “terpenes.” And specifically, in the case of balsam fir trees, the diterpenoid cis-abienol. That’s it. I’ve read perfume features pieces in Vogue that had more chemistry.

Ms. Bartels interviewed Justin Whitehill, an NC State assistant professor whom she tags as a plant pathologist. He’s actually more interesting than that. If you go to NC State’s website, you’ll see that he runs the Christmas Tree Genetics Program and that he has a grant “to develop bioluminescent Fraser fir Christmas trees.” (Dude!)

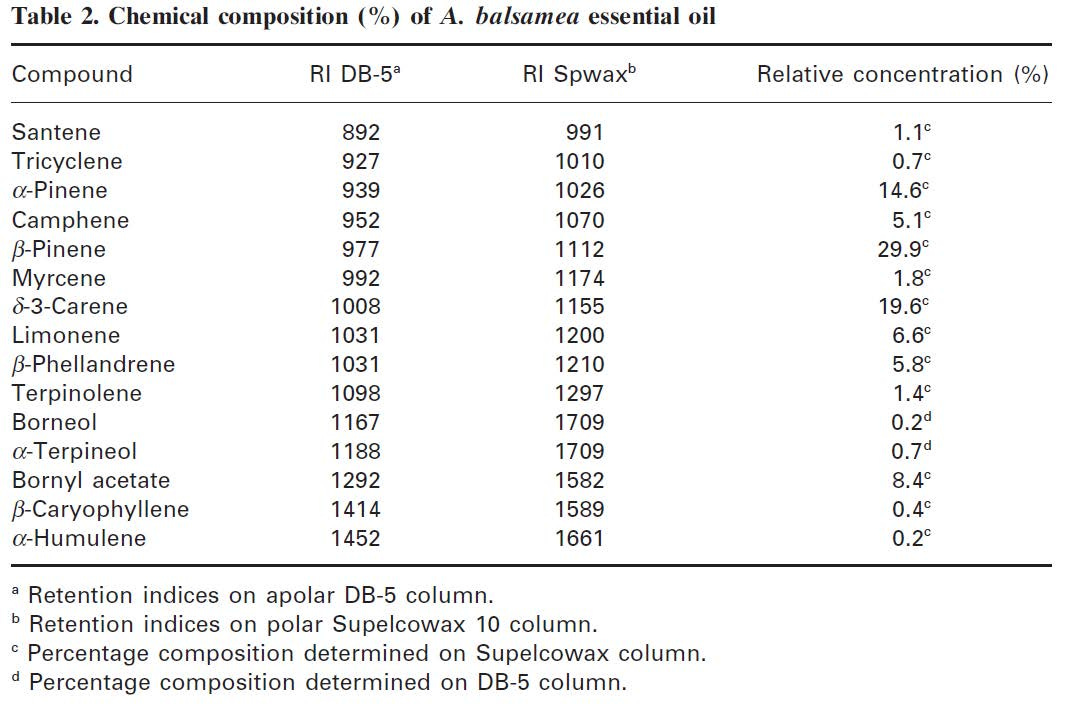

I decided to do my own digging into What Gives Christmas Trees Their Crisp, Cozy Scent. It took three minutes on PubMed to find a chemical analysis of balsam fir essential oil. It contains at least 15 common terpenes (i.e., molecules assembled from isoprene subunits), and they are just what you’d expect to find in a pine tree. Weirdly enough, many of them are also found in hops and cannabis.

Image from Pichette, et al. 2012.

Please note: the abundance of a particular scent molecule does not equal its odor impact. Some molecules pack a big punch in minute quantities; others barely register in the nose despite large concentrations. This chemical inventory doesn’t really tell you what the oil smells like.

Here is the passage where Bartels mentions a specific terpene:

In balsam firs, scientists have found a particularly interesting large terpene called cis-abienol, which is surprisingly similar in structure to a chemical long used by the perfume industry to make scents linger. Whether cis-abienol plays a similar role in Christmas trees, and whether it could be harvested for the perfume industry, remains to be determined.

What on earth is she talking about?

It took me another two minutes on PubMed to find this:

Among other applications, cis-abienol and other oxygen-containing diterpenoids of plant origin (e.g. sclareol and manool) are important in the fragrance industry to produce Ambrox, which serves as a sustainable replacement for the use of ambergris in high end perfume formulations. Whereas Ambrox is produced from plant terpenoids, ambergris is an animal product secreted from the intestines of sperm whales, which are listed as an endangered species.

Ambergris and some other compounds are useful in making perfume last longer on human skin. This is completely unrelated to the idea that cis-abienol could make balsam fir scent linger longer in the air.

Fragrance chemistry isn’t easy, but it can be explained. Just don’t expect too much from Scientific American.

Here’s hoping you don’t find a lump of coal in your stocking. Merry Christmas to all!

André Pichette, Pierre-Luc Larouche, Maxime Lebrun, and Jean Legault, Composition and antibacterial activity of Abies balsamea essential oil. Phytotherapy Research 20:371-373, 2006.

Philipp Zerbe, Angela Chiang, Macaire Yuen, Björn Hamberger, Britta Hamberger, Jason A. Draper, Robert Britton, and Jörg Bohlmann, Bifunctional cis-abienol synthase from Abies balsamea discovered by transcriptome sequencing and its implications for diterpenoid fragrance production. Journal of Biological Chemistry 287:12121-12131, 2012.