Writer Mark Hay has a new piece up at the online magazine MIC about COVID-related smell loss and how it might spur research into the mechanisms of human olfaction.

Hay, who himself suffers from reduced smell, strives to paint an optimistic picture: that COVID’s hallmark symptom of temporary or permanent smell loss will inspire new and potentially ground-breaking research. In the piece, Hay quotes a couple of patient advocates, an otolaryngologist, clinician and researcher Alan Hirsch, Monell Center researcher Valentina Parma, and yours truly.

The article is informative and its tone cautiously optimistic. Surprisingly, Hay couldn’t find any full-throated endorsements of his thesis, even among the 700 active members of the Global Chemosensory Research Consortium, led by Parma and founded in response to the pandemic’s smell issues.

The quotes I provided him by email were on the critical side. [That’s an understatement.—Ed.] Here’s one:

“Clinical research has been on autopilot” for years, argues Avery Gilbert, an independent smell researcher. “Almost no recent studies have illuminated the mechanisms of smell, or explored possible [novel] treatments for smell loss.”

Given how little enthusiasm there was for Hay’s optimistic thesis, it’s understandable that he didn’t need to draw further on my comments to achieve a balanced piece.

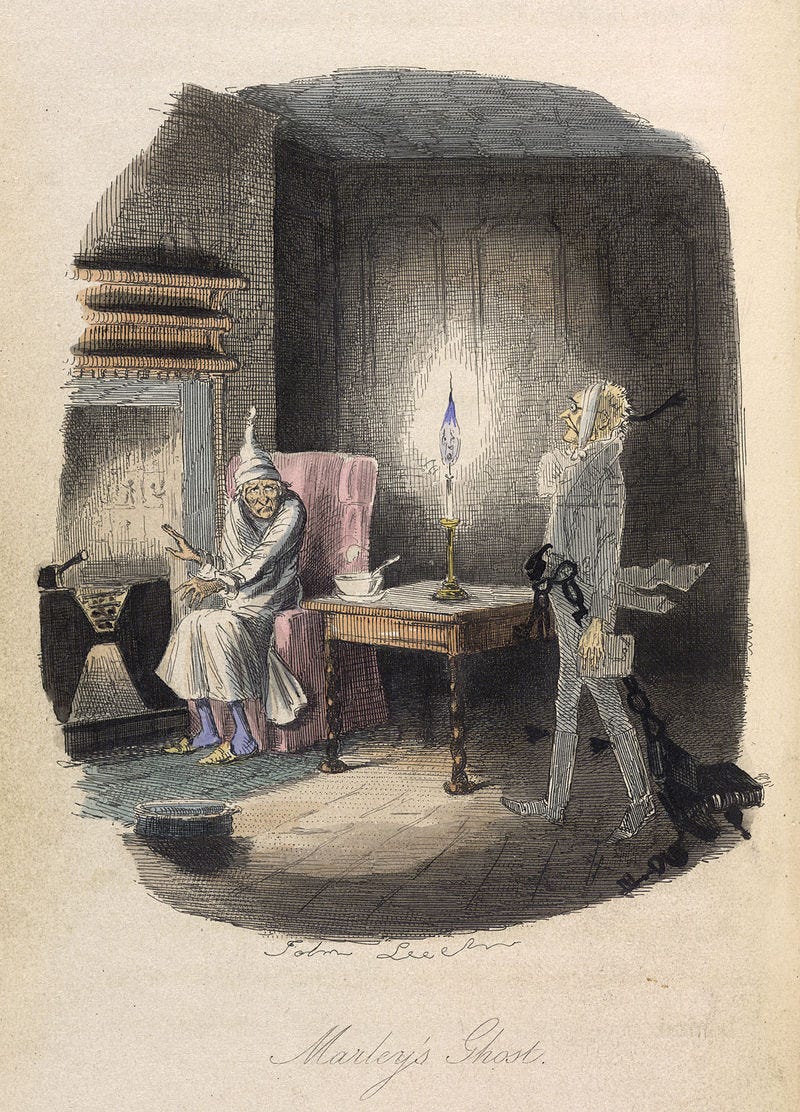

But since I’m the designated Ebenezer Scrooge in this yuletide story, let me share a bigger unpublished clip from the email interview. Here’s a vision from the Ghost of Olfaction Past.

[MH]: How would you describe the state of smell science, and attitudes towards the field, before the COVID-19 pandemic? And how do you think we reached and perpetuated that status quo?

[me]: Smell science was stalled well before the pandemic. Clinical research is on autopilot: recruit patients with disease X, give them a smell test, report the results. If X hasn’t been studied before, then okay, polite golf applause. But why keep churning out studies on reduced odor perception in Alzheimer's? That horse was beaten to death years ago. Almost none of these studies illuminate mechanisms of action or explore possible treatments.

Nor have there been any striking developments in the basic neuroscience of olfaction. It’s been 30 years since Linda Buck and Richard Axel's Nobel prize winning discovery of the mammalian odor receptor genes. Where are we now? Lots of brain imaging work, lots of hot air about AI, but no closer to understanding how the brain translates a bunch of inhaled molecules into an odor perception.

The field suffers from a lack of risk-taking. Academic scientists have become careerist: they're all about the citation metrics and the grant money. Thankfully I'm an independent and free to go explore new areas—in my case the aroma of cannabis.

Yes, I went full “Bah, humbug!” on that one. But surely things aren’t really so dire, are they? Perhaps an undigested bit of beef, or a fragment of underdone potato contributed to my bilious response. [Bullcrap. You totally believe that.—Ed.]

Here’s another give-and-take that didn’t make it into the story, a vision from the Ghost of Olfaction Future.

[MH]: Might some of these new resources, collaborative efforts, and/or projects advance not just our understanding of the effects of COVID-19 and how to address them, but our understanding of and approaches to olfaction overall? If so, how?

[me]: Not likely. When it comes to regular flu, we understand the clinical picture of smell loss pretty well. The older you are, the more vulnerable you are. The greater your initial deficit, the longer it takes to recover and the less likely you are to recover fully. Is COVID-19 substantially different? It doesn't appear to be. Sure, it attacks different cells in the nose, and yes in some cases it creeps into the brain with unpleasant consequences. But smell-wise it’s a similar clinical picture.

No surprise that didn’t make print. It doesn’t really fit the Pandemic Panic narrative. [Or you just could be full of crap.—Ed.] [I could be. I’m just an Average Joe. But I’m willing to debate the point with any of the 700 active members of GloboCov.]

Here again note that almost all the research effort on COVID smell loss is focused on detection/diagnosis. There’s very little on treatment, e.g., what sort of pharmacologic intervention would lessen COVID impact on the olfactory epithelium or speed its recovery?

Now that’s something to go after! What a fine, fat Christmas turkey to deliver to the hyposmic Cratchits of the world.